- What dynamics or combinations of pathways encode specific cell fate choices?

- How are signaling pathways repurposed for different functions depending on cell type?

- How much spatial and temporal information can be encoded by each pathway?

To make headway on these questions we take advantage of a number of tools, especially

- Optogenetics

- High-resolution microscopy

- Biochemistry/cell biology

- Systems biology

- Signal processing

- Control theory

Cellular optogenetics - controlling protein activity in time and space

How do cells store and process information about their environment? We know this process is complex: natural stimuli like growth factors and stresses activate signal transduction at specific locations in the cell, and often generate complex activity patterns: pulses, traveling waves, or even oscillations. However, we lack experimental tools to induce these patterns on demand. Our understanding would be transformed if we could "reach into the cell" to activate a single signaling protein in a live cell, exactly when and exactly where we want. To achieve this goal, my lab is working to develop new approaches for cellular optogenetics, enabling us to precisely control protein activity using light. Unlike diffusible chemical stimuli, light can activate a desired protein species without off-target effects, and the intensity of activation can be exquisitely controlled with high spatial and temporal resolution.

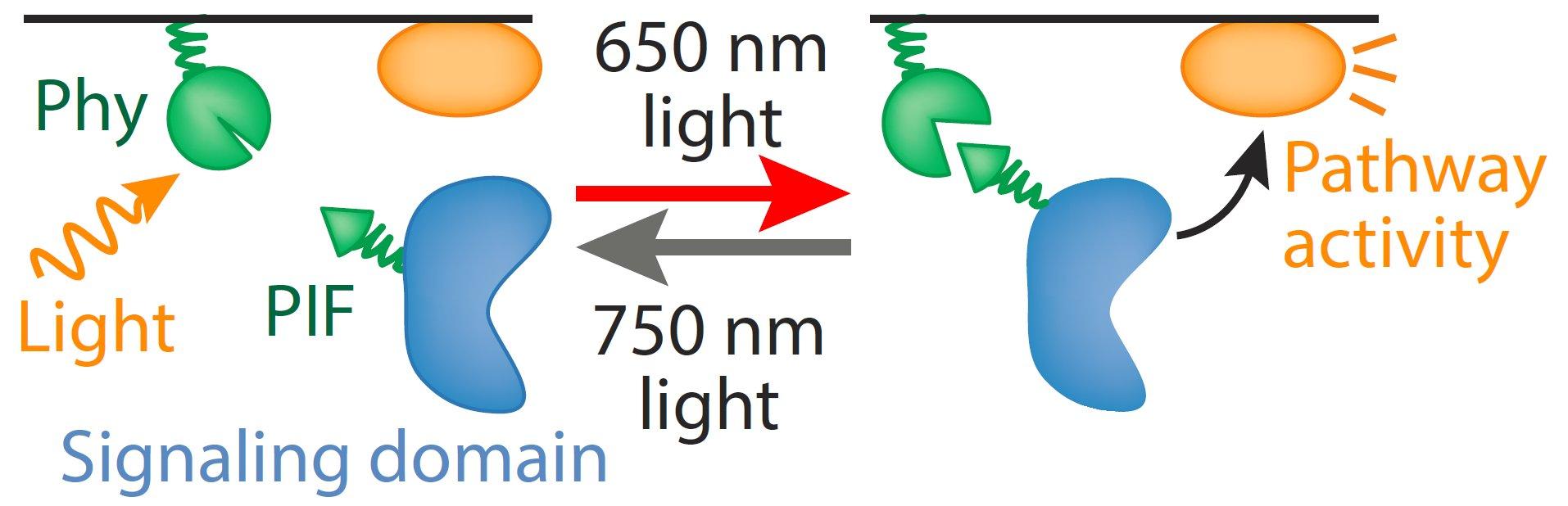

The Toettcher lab focuses especially on the light-gated interaction between Phytochrome B and PIF6 Arabidopsis thaliana, commonly referred to as the Phy/PIF system. By fusing Phy and PIF to proteins of interest, it is possible to reversibly control their association (and in many cases, signaling output) by applying different levels of two light wavelengths: 650 nm red light to drive association, and 750 nm far-red light to drive dissociation. This two-wavelength control makes it possible to control signaling with high spatial and temporal accuracy, even achieving "grayscale" control by varying the relative intensity of both wavelengths. Our lab seeks to

- improve these technologies by building the next generation of optogenetic tools

- expand their scope to control key intracellular events

- develop approaches to integrate light stimulation with more complex biological systems (multi-color experiments and model organisms)

Signal processing across cellular contexts

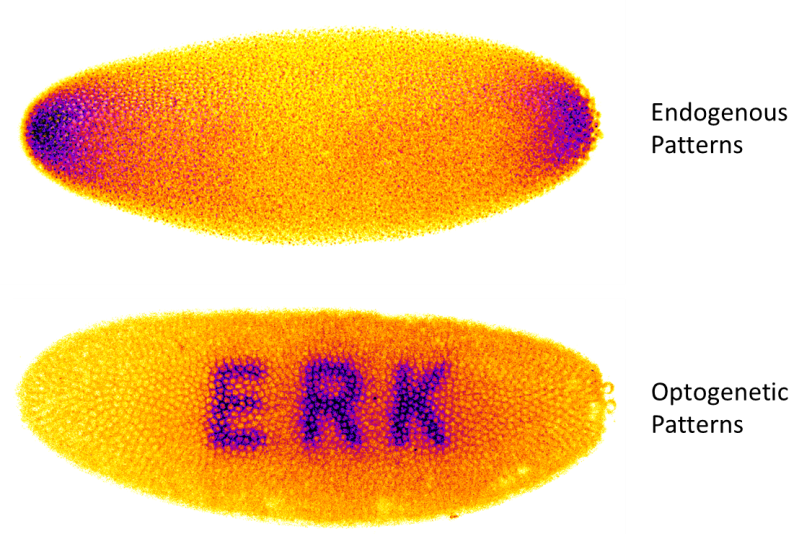

During development, elaborate patterns of signaling protein activity arise one after another to turn on genes and create differentiated tissues. For many years, genetic approaches have been used to perturb and study these patterning events. However, while genetics offers extremely powerful tools for controlling the absence or presence of pathway components entirely, it is rather ill-suited to precisely define the timing, dynamics, intensity, or spatial range of these patterns. Greater control is required to truly understand what features of these patterns are actually read and used to specify future tissues. Using optogenetics we can “paint” patterns of signaling onto the blank canvas of the early embryo and begin to answer questions which would have been next-to-impossible to otherwise address:

During development, elaborate patterns of signaling protein activity arise one after another to turn on genes and create differentiated tissues. For many years, genetic approaches have been used to perturb and study these patterning events. However, while genetics offers extremely powerful tools for controlling the absence or presence of pathway components entirely, it is rather ill-suited to precisely define the timing, dynamics, intensity, or spatial range of these patterns. Greater control is required to truly understand what features of these patterns are actually read and used to specify future tissues. Using optogenetics we can “paint” patterns of signaling onto the blank canvas of the early embryo and begin to answer questions which would have been next-to-impossible to otherwise address:

What features of signals pattern tissues? What level of spatial precision is required by these patterns? And finally, when during development are cells able to perceive these external cues?

In addition to these questions, the precise timing and control of optogenetics often allows us better understand the mechanisms behind classic developmental phenotypes. For example, suppose a gain-of-function mutant gives a particular end-point phenotype. It is often unclear what the root cause of this phenotype is, as a particular end-state could result from the convolution of multiple disrupted events in different cells that occur at different times or at different locations. In this all-too-common common situation it can be difficult, if not impossible, to dissect the molecular origins of the observed response. In contrast, light-based activation can be limited to a particular cell type, position or developmental time. This allows us to directly tie phenotypes to a minimum set of altered cell fate decisions, enabling us to dissect classic embryonic phenotypes in a whole new light.

Photoswitchable reagents for tissue-level control

Coming soon!

Recent Publications

Contact

Toettcher Lab

Department of Molecular Biology

138 Lewis Thomas Laboratory

Washington Road

Princeton, NJ 08544

Phone: 609-258-9243

Faculty Assistant

Ellen Brindle-Clark

230 Lewis Thomas Laboratory

[email protected]

Phone: 609-258-5419